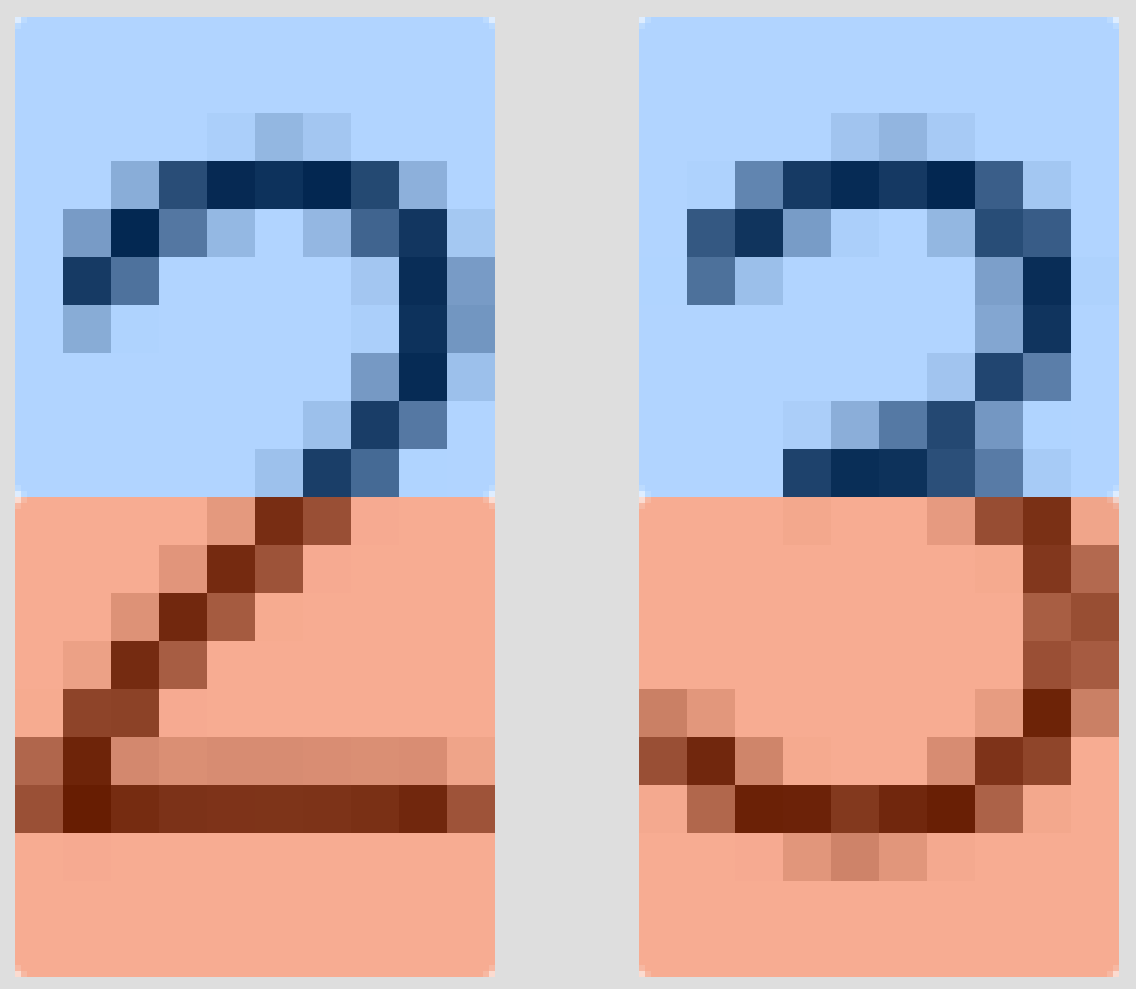

def digitSet2Vec(path: String): Seq[DenseVector[Double]] = {

val selector: Int => Boolean = _ < 255 // Our selector, 0 for a white (255) pixel, 1 for everything else

(0 to 9) map (i => extractBinary(getResourceFile(path + s"$i.png"), selector)) // Image flattened as vector

}

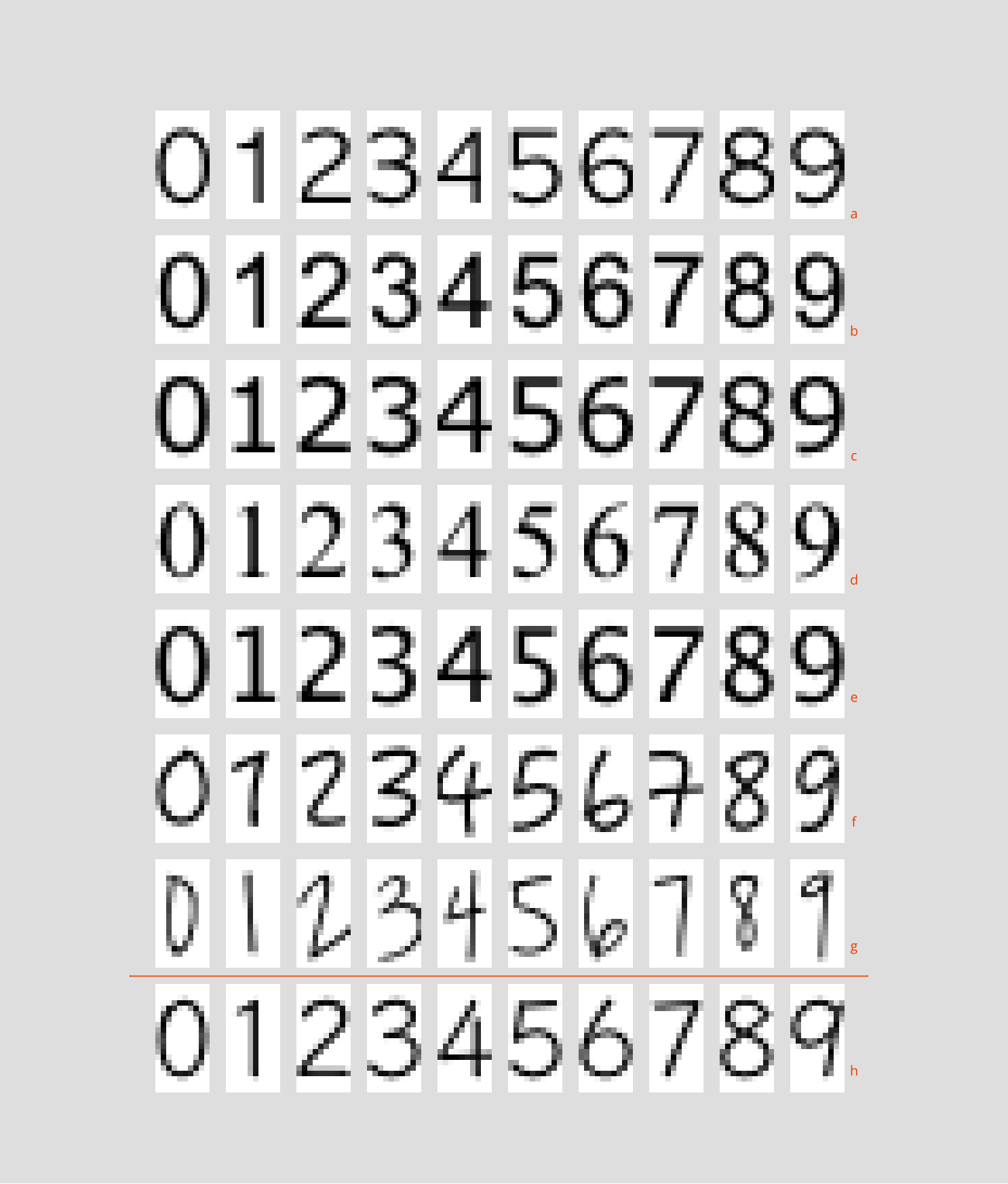

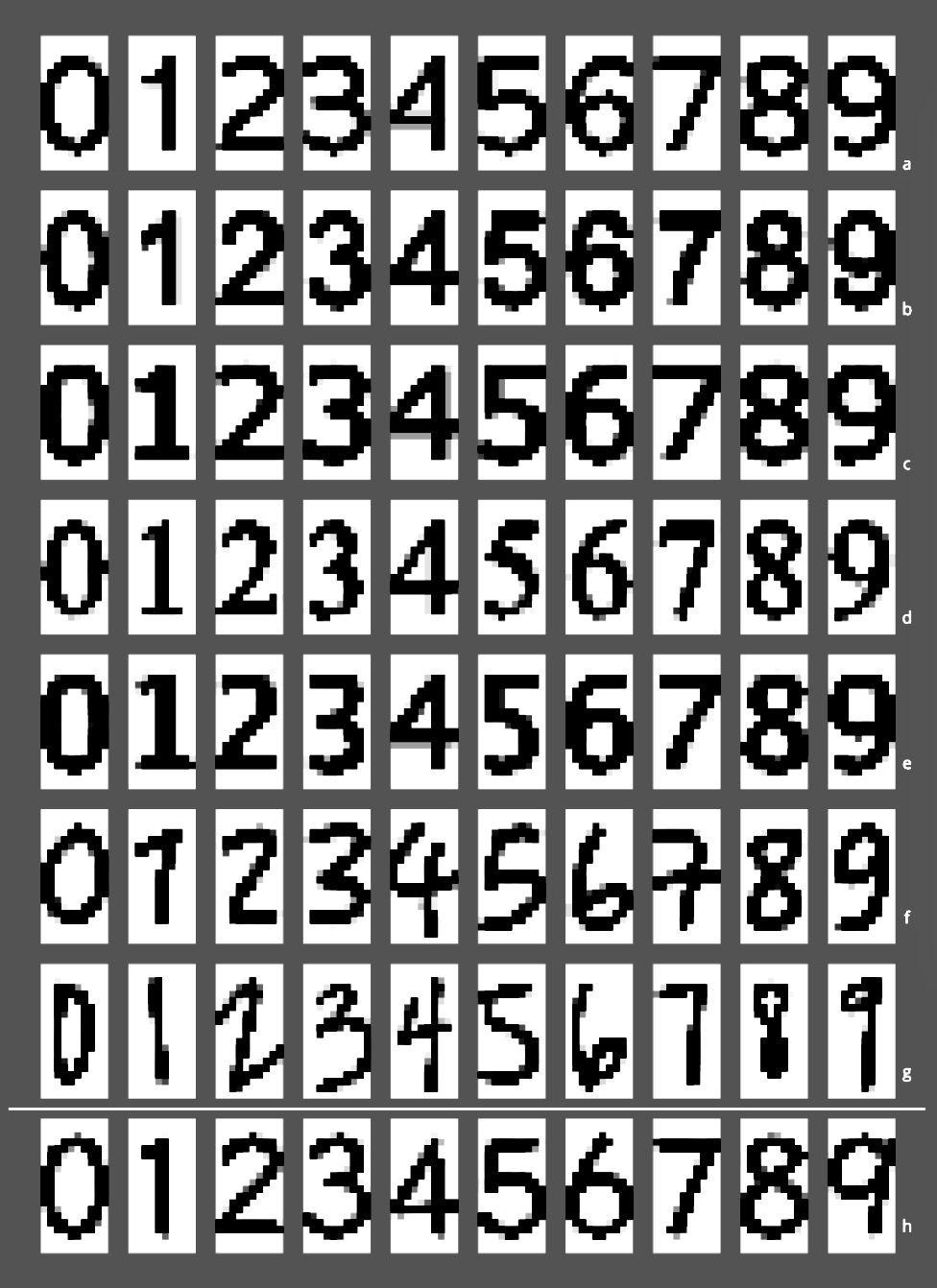

val sets = ('a' to 'h') map (c => getDigitSet(s"img/digits/$c/"))

val xs = sets.dropRight(1).flatMap { s => (0 to 9).map { digit => s(digit) } }

val ys = sets.dropRight(1).flatMap { m => (0 to 9).map { digit => ->(0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0).updated(digit, 1.0) } }

val config = (0 to 2).map(_ -> (0.01, 0.01)) :+ 3 -> (0.1, 0.1)

implicit val breeder = neuroflow.core.WeightBreeder[Float].normal(config.toMap)

val f = ReLU

val net = Network(

layout =

Vector (200) ::

Dense (400, f) ::

Dense (200, f) ::

Dense ( 50, f) ::

Dense ( 10, f) :: SoftmaxLogEntropy(),

settings = Settings(

learningRate = { case (_, _) => 1E-5 },

updateRule = Momentum(0.8f),

precision = 1E-3,

iterations = 15000

)

)

net.train(xs, ys)

_ __ ________

/ | / /__ __ ___________ / ____/ /___ _ __

/ |/ / _ \/ / / / ___/ __ \/ /_ / / __ \ | /| / /

/ /| / __/ /_/ / / / /_/ / __/ / / /_/ / |/ |/ /

/_/ |_/\___/\__,_/_/ \____/_/ /_/\____/|__/|__/

Version : 1.3.4

Network : neuroflow.nets.cpu.DenseNetwork

Loss : neuroflow.core.Softmax

Update : neuroflow.core.Momentum

Layout : 200 Vector

400 Dense (R)

200 Dense (R)

50 Dense (R)

10 Dense (R)

Weights : 170.500 (≈ 0,650406 MB)

Precision : Single

O

O

O O O

O O O

O O O O O

O O O O O

O O O

O O O

O

O

[run-main-0] INFO neuroflow.nets.cpu.DenseNetworkSingle - [14.12.2017 17:03:26:824] Training with 70 samples, batch size = 70, batches = 1 ...

Dez 14, 2017 5:03:26 PM com.github.fommil.jni.JniLoader liberalLoad

INFORMATION: successfully loaded /var/folders/t_/plj660gn6ps0546vj6xtx92m0000gn/T/jniloader31415netlib-native_system-osx-x86_64.jnilib

[run-main-0] INFO neuroflow.nets.cpu.DenseNetworkSingle - [14.12.2017 17:03:27:090] Iteration 1 - Loss 0,842867 - Loss Vector 1.3594189 1.0815932 0.06627092 1.2282351 0.40324837 ... (10 total)

[run-main-0] INFO neuroflow.nets.cpu.DenseNetworkSingle - [14.12.2017 17:03:27:152] Iteration 2 - Loss 0,760487 - Loss Vector 1.2405235 1.0218079 0.080294095 1.1119698 0.30945536 ... (10 total)

[run-main-0] INFO neuroflow.nets.cpu.DenseNetworkSingle - [14.12.2017 17:03:27:168] Iteration 3 - Loss 0,631473 - Loss Vector 1.0470318 0.9293458 0.10742891 0.92295074 0.16466755 ... (10 total)

[run-main-0] INFO neuroflow.nets.cpu.DenseNetworkSingle - [14.12.2017 17:03:27:178] Iteration 4 - Loss 0,528371 - Loss Vector 0.8682083 0.8433325 0.17737864 0.7455 0.062339883 ... (10 total)

[run-main-0] INFO neuroflow.nets.cpu.DenseNetworkSingle - [14.12.2017 17:03:27:188] Iteration 5 - Loss 0,439425 - Loss Vector 0.6963819 0.7676125 0.23556742 0.5764897 0.062838934 ... (10 total)

('a' to 'h') zip setsResult foreach {

case (char, res) =>

println(s"set $char:")

(0 to 9) foreach { digit => println(s"$digit classified as " + res(digit).indexOf(res(digit).max)) }

}

|

Set A 0 classified as 0 1 classified as 1 2 classified as 2 3 classified as 3 4 classified as 4 5 classified as 5 6 classified as 6 7 classified as 7 8 classified as 8 9 classified as 9 |

Set B 0 classified as 0 1 classified as 1 2 classified as 2 3 classified as 3 4 classified as 4 5 classified as 5 6 classified as 6 7 classified as 7 8 classified as 8 9 classified as 9 |

Set C 0 classified as 0 1 classified as 1 2 classified as 2 3 classified as 3 4 classified as 4 5 classified as 5 6 classified as 6 7 classified as 7 8 classified as 8 9 classified as 9 |

Set D 0 classified as 0 1 classified as 1 2 classified as 2 3 classified as 3 4 classified as 4 5 classified as 5 6 classified as 6 7 classified as 7 8 classified as 8 9 classified as 9 |

|

Set E 0 classified as 0 1 classified as 1 2 classified as 2 3 classified as 3 4 classified as 4 5 classified as 5 6 classified as 6 7 classified as 7 8 classified as 8 9 classified as 9 |

Set F 0 classified as 0 1 classified as 1 2 classified as 2 3 classified as 3 4 classified as 4 5 classified as 5 6 classified as 6 7 classified as 7 8 classified as 8 9 classified as 9 |

Set G 0 classified as 0 1 classified as 1 2 classified as 2 3 classified as 3 4 classified as 4 5 classified as 5 6 classified as 6 7 classified as 7 8 classified as 8 9 classified as 9 |

Set H 0 classified as 0 1 classified as 1 2 classified as 2 3 classified as 3 4 classified as 4 5 classified as 5 6 classified as 6 7 classified as 7 8 classified as 8 9 classified as 9 |